I’m in death-tech. I advance cutting-edge technology in the funeral industry with software. It might be easy to think that I would hear about a historical exhibit on cremation, and keep scrolling. But to do that would be to negate the background of this entire genre of service. Some people don’t see how technology and history go together. In my view, technology evolves from history and then takes a big, cold shower in innovation. To move ahead in our industry, I felt I must first take a step back. Join me.

The National Museum of Funeral History has been in my heart since mortuary school. The beautiful displays remain every death-care professional’s Instagram playground, and this visit was no different. When I arrived, I noticed the large brick-building display tucked toward the back looked like it had always been there. As though to say, cremation has always had a place in our history.

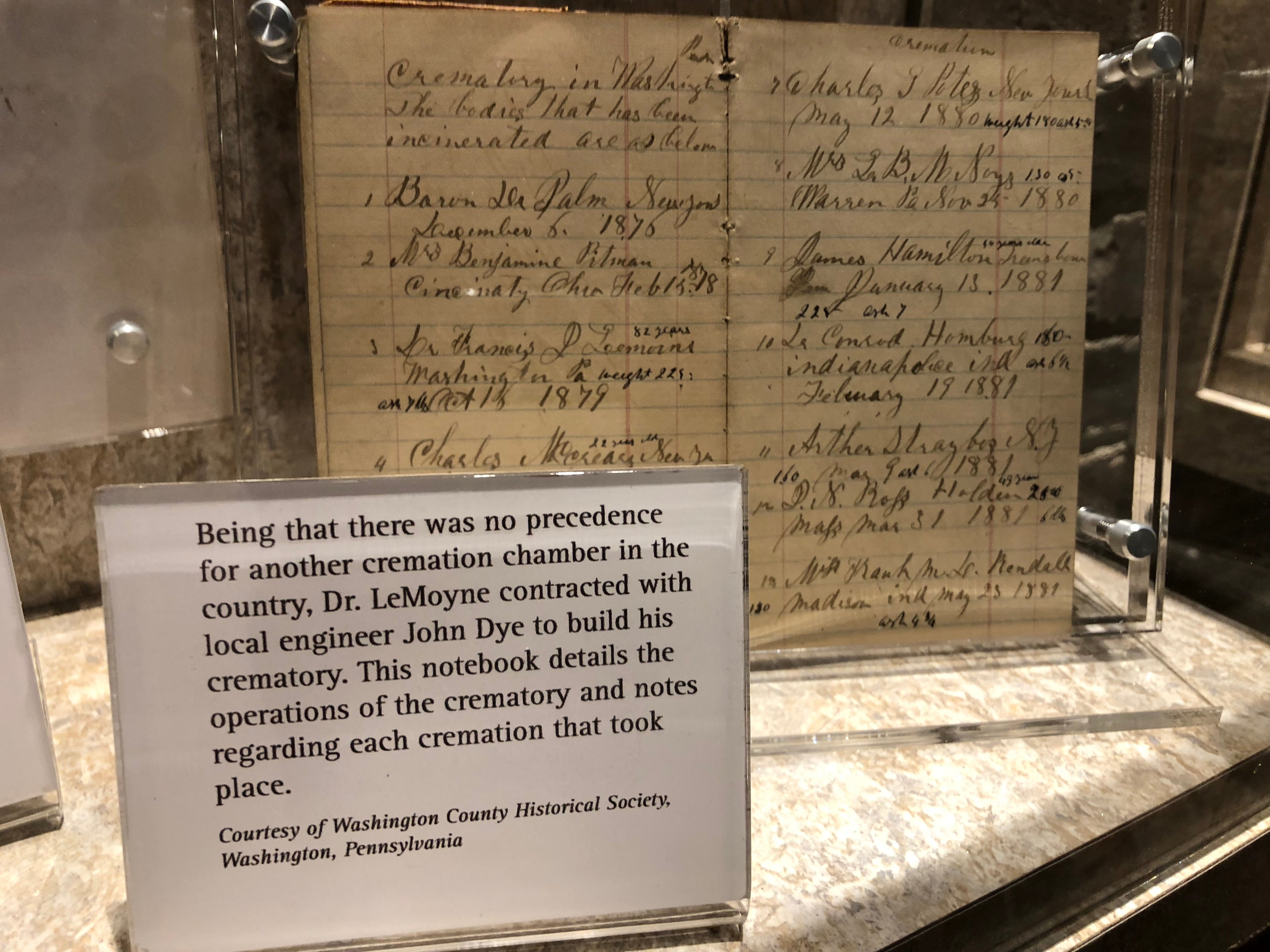

Inspired by the LeMoyne Crematory, the first crematory built in America in 1876, the exhibit’s design lends itself to the historic nature of its title. Francis LeMoyne was a doctor who preferred cremation for sanitation purposes. After cemeteries rejected his dispositional desires, he built his own crematory. The exhibit’s first room encases written artifacts, such as the notebook of John Dye, the builder, designer and operator of the crematorium. The first cremation was an exclusive event offered to the medical science community. Yes, science existed in 1876. Yet, cremation attracted the curious in droves. An illustration of LeMoyne’s Crematory later ran in The New York World Magazine. Even then, the underpinnings of mild rebellion, curiosity, and science all swirled together. It reminded me of today’s discussions of the changing climate of death-care.

The exhibit showed the chronology of cremation in America, from ornate crematoria design to an interactive retort. Visitors can even “push the button” to activate a televised explanation of the cremation process. On into the urn room, an “urn-dertaking” by any stretch of the imagination! The vast collection gives viewers a hardy visual of urn designs through time.

Then a mother of pearl urn caught my eye, hanging out on the wall by itself. Jason Engler, CANA’s Cremation Historian and my personal tour guide, explained how this particular urn survived Hurricane Harvey. As memories of the hurricane waters came flooding back, I teared up at the thought of how many of our lives were permanently changed. Yet, that context yielded a renewed vigor for the celebration of new life. Technology, even in materials, can make what was old, broken, or washed away, better than ever.

The final space is filled with today’s resources for cremation. Everything from memorial jewelry to blown-glass ornaments, life-giving urns, and more. There is even new art created from cremated remains by the talented Heide Hatry, creator of “Icons in Ash.” Hatry worked through her unresolved grief by creating portraiture in her father’s likeness, then those of others who have passed. I shared what I do, the death-tech side of the industry. A look of surprise came over her face, one I’ve seen before. People are usually surprised at the concept of death-tech. Once they think about how it’s used, they understand the appeal.

I concluded my tour by chatting up Genevieve Keeney, President of the NMFH. We casually discussed our thoughts about the business, museum, and profession from the perspective of two powerful women. Women in death-care are advancing at a record pace and moving into more leadership roles than ever. As a visionary, Genevieve understands that the historical context of our profession is what gives us our beginning. Ultimately, the exhibit and its visitors give the impression of a new generation in the industry, rising from the ashes.